Sago 20 Years Later

Mining tragedy’s effects still linger

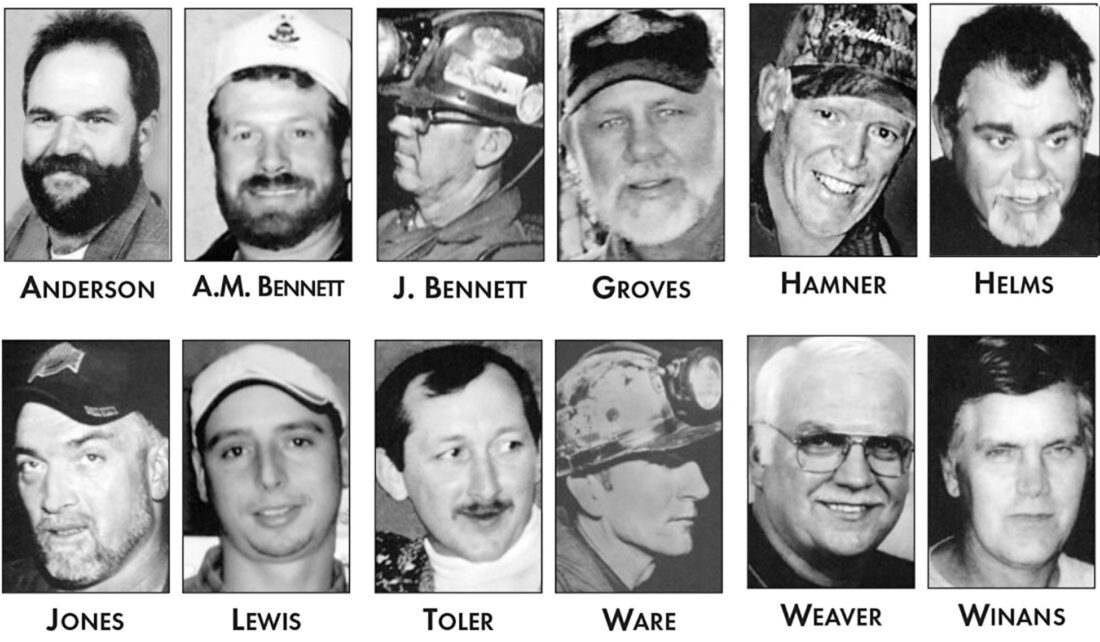

- Submitted photo A memorial in honor of the 12 Sago miners who lost their lives was placed by the historic Covered Bridge in Philippi. Three of the men who died in the accident were from Barbour County.

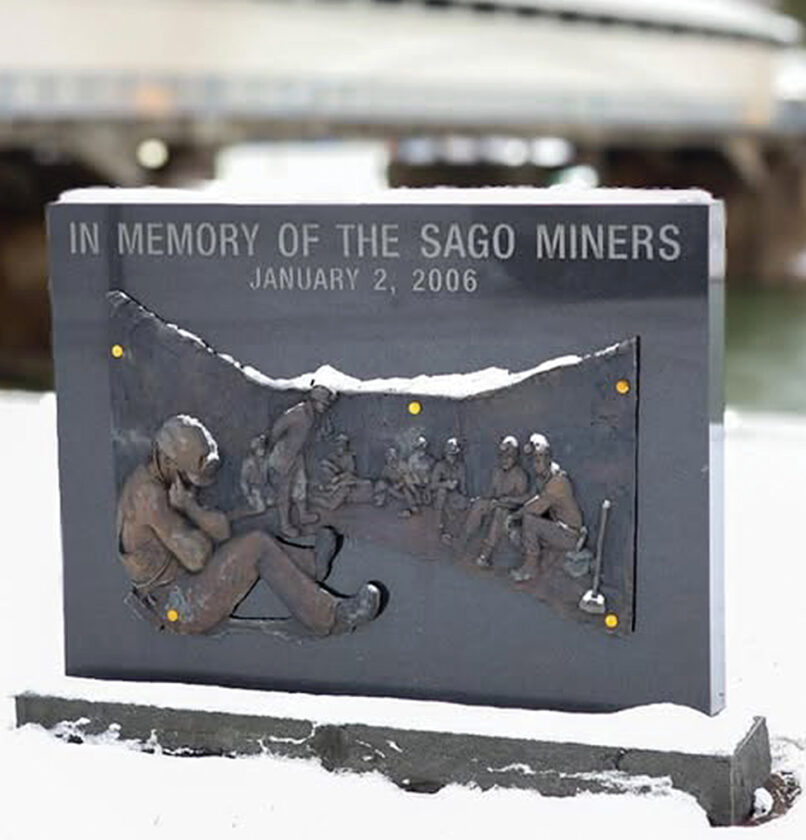

- Submitted photo A memorial honoring all 12 miners who died in the disaster is located at the Sago Baptist Church in Buckhannon. Every year on Jan. 2, mourners come to pay their respects at the memorial.

SAGO — 20 years ago today, 12 West Virginians lost their lives in one of the worst coal mining disasters in the state’s history.

On Jan. 2, 2006, an explosion and collapse in the Sago mines trapped 13 miners underground for nearly two days. Only one man survived. In the days, and even weeks after, the area was at the center of national attention as friends, families, community members and the state grieved over the loss of 12 of their own.

State Senator Bill Hamilton remembers the night of the explosion, and the harrowing aftermath, well. A representative for Upshur County in the state House of Delegates at the time, Hamilton recalled falling asleep on the couch the night before after watching the West Virginia Mountaineers’ victory in the 2006 Sugar Bowl.

“About 6:30 a.m. (on Jan. 2), about the loudest thunder I’ve ever heard in my life woke me off the couch, and then I found out a couple hours later that there was a mine explosion at Sago,” Hamilton told The Inter-Mountain. “I mainly thought of a couple of my clients and a good friend of mine from high school that was working in the mine, and I was praying that they weren’t involved in the disaster, but they were on the crew that was trapped in the mine at the time.”

Hamilton’s high school friend was George Junior Hamner, who Hamilton said they always called “Junior” during their school days. The two had been locker mates from ninth grade until they graduated.

Submitted photo A memorial in honor of the 12 Sago miners who lost their lives was placed by the historic Covered Bridge in Philippi. Three of the men who died in the accident were from Barbour County.

Hamilton, along with other representatives and officials, like Shelley Moore Capito and then Governor Joe Manchin, went to the site of the explosion, joining the miners’ family members as the rescue efforts began.

Hamilton recalls seeing several media trucks as he headed towards the Sago Baptist Church where the families were gathered. As he entered, a representative with the Red Cross handed Hamilton a list with names of the 13 trapped miners, and there he saw the names of two clients and Hamner.

“Those three days that we were involved with Sago and trying to rescue those guys, I mean the community really came together for the miners and for the miners’ families,” Hamilton said. “Of course, I’m a little biased. I’ve lived here all my life… I was really impressed with the support for the miners and their families.”

When the incorrect news broke that all 13 of the miners had been rescued, Hamilton says he admittedly felt it was “a little odd” and “unusual” that the miners were allegedly going to be brought out of the mine and taken to the church “to eat dinner.” After three hours, however, it was revealed that only one miner, Randal L. McCloy Jr., had survived.

“I really felt badly for Governor Manchin and for the people with ICG (International Coal Group, Inc.) that came out and had to make the announcement that they had it wrong,” Hamilton said. “That there was 12 miners deceased and one rescued. It was a very sad time.”

Submitted photo A memorial honoring all 12 miners who died in the disaster is located at the Sago Baptist Church in Buckhannon. Every year on Jan. 2, mourners come to pay their respects at the memorial.

Hamilton also recalled that about a week later, during a memorial service for the 12 miners at West Virginia Wesleyan College, members of the Westboro Baptist Church in Topeka, Kansas showed up to protest the memorial. He said the group claimed that the accident was God’s revenge against the United States for its tolerance of homosexuality. Students at Wesleyan, however, did not tolerate the display.

“I was really proud of the students at West Virginia Wesleyan… (the Westboro Baptist Church) had set up a picket line where the families would enter, so the students went down, on their own, and they formed a picket line in front of those protesters,” Hamilton said. “(The Westboro Baptist Church) complained to the law enforcement, and law enforcement said ‘Well, the students have just as much a right to protest as you do.’ (The students) shielded the miners’ families from those protesters.”

Every Jan. 2, Hamilton does his best to join the miners’ families in remembering and honoring the 12 miners lost at the Sago Baptist Church, where a memorial stands for the men.

Rescue efforts at the time of the incident were handled on both the professional and local level. Mike Ross, president of Mike Ross, Inc., recalled how his company helped bring a drilling rig to the site to drill an airhole down into the mine for the 13 men.

“I’d been up at the mines that morning, asking if I could help because we had a small drilling rig working close by,” Ross told The Inter-Mountain. “First they said ‘No, we think we can handle it,’ and then I was having lunch at Pizza Hut with a drilling contractor, and they sent an emergency squad out and located me and asked if I could come up to the mines and give them a hand.”

After the area was surveyed, the rig was brought and Ross remembers how they had to deal with rain and snow as they worked on the airhole. His focus at the time was on trying to get a sign of life from the miners, and ensuring the men would be able to breathe while underground.

“If we could get close to them and get some signal back from them indicating they were alive, we would get fresh air to them,” Ross said. “The (mine) inspectors had shut off all the fresh air into the mine because, had the mine been burning, if you’re pumping oxygen into it, the fire would have gotten larger… We didn’t know (if the mine was burning). We couldn’t tell.”

Ross explained that they started drilling the hole around 2 p.m. and had gone approximately 250 feet “straight down” in two hours. The workers beat sledgehammers against the drill pipe in the hole, sending a signal down to try and get a signal back from the miners; however, they heard nothing back.

“Come to find out after a couple of days and drilling a couple more holes, we were within 400 feet of (the miners) on the first hole,” Ross said. “They were huddled up in there, one of them still alive out of 13. It was just a sad day and then come to find out, when it was all over, that mine was not burning… and (the miners) were less than two miles underground.”

Ross also recalled that the surviving miner, McCloy, may have heard the sounds of the sledgehammers hitting the drillpipe, but did not respond.

One crucial moment in the entire event was the misinformation given out that all 13 of the miners had been found alive and rescued. News media at the time were quick to report on the supposed miracle, only to have to retract the story later once it was clarified that only McCloy survived. One local media outlet that did not report the incorrect information was The Inter-Mountain.

Linda Howell Skidmore, who was The Inter-Mountain’s editor at the time of incident, recalled being on the phone with two reporters at the same time after the news broke that all 13 men had been rescued. One reporter, Joey Kittle, was in the Elkins office, watching the Associated Press’ reporting on the event, and the other, Becky Wagoner, was on the scene at Sago, watching the situation in real time.

“(Wagoner) was at the staging area and we were talking and she said ‘Oh, there’s all this excitement of everyone saying all of the miners are safe and they’ve all been rescued,’ but she said there’s something not right because only one ambulance came out,” Skidmore told The Inter-Mountain.

“(Wagoner) said if they’re all safe there would be more ambulances, and she kept waiting there and she said ‘No, there are no more. There was only one ambulance.’ So that’s when the three of us said, ‘Okay, hold up. Something’s not right.'”

Skidmore said The Inter-Mountain held off on putting out any information until reporters were informed that their suspicion was correct and there was only the sole survivor. As Skidmore explained, the paper followed the philosophy of “Do you want to be first or do you want to be right?” Despite The Inter-Mountain’s correct suspicion that the initial information was inaccurate, Skidmore admitted that, at the time, there was some hope they were wrong.

“When you’re reporting things like that, you have hope. You report on tragic situations and, if you do this a long time, you see a lot of things that aren’t good,” Skidmore said. “A lot of tragedies… but when you’re in that mode of gathering information, your personal emotions, you have to put that aside and deal with what you’re seeing and what the facts are…Once you’ve done your job, that’s kind of when the emotions come out.”

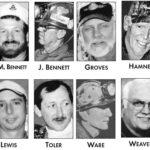

The miners who lost their lives in the Sago Mine Disaster included:

* Tom Anderson, 39, of Rock Cave. He was married to Lynda Hyre Anderson and was father to Caleb, Randy, Mitchell and Thomas Isaac.

* Jerry Lee Groves, 56, of Cleveland, Webster County. He was married to Deborah A. Groves and was father to Shelly Rose.

* James Bennett, 61, of Volga. He was married to Lily Foster Bennett and was father to Ann Merideth and John.

* George Junior Hamner, 54, grew up on a farm near the site of the Sago Mine and owned a small cattle farm in Glady Fork. He was married to Deborah Hamner and father to Sara Bailey.

* Marty Bennett, 51, of Buckhannon. He was married to Judy Ann Lantz Bennett and father to Russell, who also worked at the Sago Mine.

* Terry Helms, 50, of Newburg, Preston County. The father of Amber and Nick, from a previous marriage. Helms was engaged to be married to Virginia Moore.

* Jesse L. Jones, 44, of Pickens. He was the father of two daughters, Sarah and Katelyn.

* Fred G. Ware, Jr., 59, of Tallmansville. He was the father of a daughter, Peggy Cohen, and a son, Darrell.

* David Lewis, 28, of Thornton, Taylor County. He was married to Samantha Lewis and was father to Kayla, Shelby and Kelsie.

* Jackie Weaver, 51, of Philippi. He was married to Charlotte Poe Weaver and was father to Rebecca and Justin.

* Martin Toler, Jr., 51, of Flatwoods. He was married to Mary Lou Toler and was father to Courtney and Chris, who had worked with his father in another mine.

* Marshall Winans, 50, of Belington. He was married to Pamela Pharis Winans and was the father of three daughters, Tiffany, Mandy and Holly.