Kirelawich’s surprise Hall of Fame induction

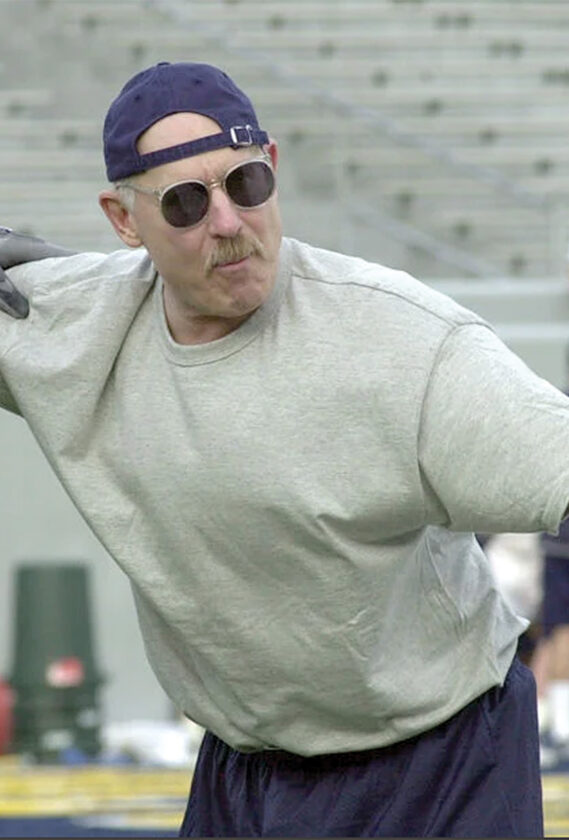

Kirelawich

MORGANTOWN — The phone call he received a while back left Bill Kirelawich speechless, as it was a condition he seldom had ever found himself in and most fortunately for all of us was only a temporary condition.

But he didn’t have many words when the voice on the other end of the line was informing him he had been selected to go into the West Virginia University Hall of Fame.

Hall of Fame?

“You never expect anything like that,” he said.

This wasn’t a person who starred in football at WVU. He wasn’t someone who had a head coaching resume’ there.

He was an assistant football coach for 37 years, 32 of them at WVU. Truth was, Tony Caridi once tried to have him explain his “career” as a coach on his podcast and he had corrected him. To Bill Kirelawich, he didn’t have a career, just a job.

“Careers,” he told Caridi, “are for movie stars and baseball players. I had a job.”

Halls of Fame are for guys who have careers. For goodness sake, Pete Rose hasn’t been able to get into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

“I wasn’t as good a coach as Pete Rose was a baseball player,” he said the other day.

He was just an ordinary guy, a working class stiff who enjoyed a cigar and a beer, the guy at the end of the bar, which was fitting, for his father owned a bar and the family lived upstairs.

Just a regular guy who understood hard work and who loved football and who would spend much of his career with Don Nehlen, even though they were hardly cut from the same cloth in anything but coaching football.

“Don hated when I cursed. He never told me not to, but he let me know. He hated when I chewed, but he never told me not to. He hated when my car was dirty. For me, the garbage dump was the back seat. I’d be driving down the road, grab a stick of gum and the wrapper would go in the back seat,” Kirelawich said.

“My car was always messy but he was fickle for a clean car. His idea of having a good time was going home after practice and waxing his car. I never waxed my car as long as I had one. I had a hard time convincing him that when I had a car, that car was there to serve me, not the other way around.

“He was always on me about my driving. One time I remember Pat Randolph had just committed to us and we’re driving down the road. I can’t see too good at night, even then. It was two lanes and it turned into a one-lane road and I didn’t see it.

“There was a sign in the middle, with an arrow, I went right up over that son of a gun, down the other side and kept going . He wasn’t too happy about that and didn’t care who I just committed.”

That was a long time ago and he’s since then had cataract surgery.

“I see as good as Superman now,” he said.

His name may have been Bill but he was just a regular Joe who could really coach and the main trait of WVU’s glory years football teams under Nehlen was defense.

So what makes a Hall of Fame assistant coach?

“That’s like asking Ted Williams how to hit a baseball,” Kirelawich replied the other day.

The Ted Williams reply is not surprising, for Kirelawich is an avid baseball fan who lives part of the year in Bradenton, Fla., and spends a lot of his life watching baseball games.

But what makes a Hall of Fame assistant coach?

“You’re asking me to dig down deep. I never got into them and their girlfriends much. I never asked questions I didn’t want to know the answer to and if a kid needed time, I gave them time. I don’t know. Like I said, I treated them like I wanted to be treated.

“I didn’t let them use the trials we go through in life. Look, everybody’s got a story. Chances are, if they are playing football, there’s tough times in everybody’s life. You’re not different because you have those tough times. What makes you different is how you overcame those tough times; how you play through it. That’s something you don’t have to put out there in front of everybody. That’s something you have to get through yourself.

“You have to get through it yourself and I didn’t want to make it any tougher.”

His secret was that he treated them the way he would want to be treated. Rough love, nothing too personal, just a guy doing a job with a lot of kids living out their dreams as they played football and worked toward a degree, just as he had when he left eastern Pennsylvania coal mining and mill country to play at Salem College in West Virginia.

Kirelawich discovered WVU then, joined the staff at WVU as a graduate assistant and became a full-time assistant in 1980, Nehlen’s first year and was there for the opening of Mountaineer Field.

He remembers the scene, with the governor on hand, John Denver on hand to sing “Country Roads,” a sold out house to start a new era.

“I said to myself the same thing I said when I went to Arizona to coach Rich Rodriguez,” he recalled. “What the hell am I doing here? It was a great day. Of course, we didn’t get to hear John Denver sing because we were in the locker room then, but that’s what started everything off.”

He outlasted Nehlen at the school, living the blue collar existence that he preached and that Nehlen made a trademark of his teams.

Kirelawich was content. Did he ever want to become a head coach?

“No,” he answered.

Why not?

“Because of the kids at the time, that would have meant I had to spend more time away from my kids,” he said. “I thought West Virginia was the perfect place for me. I liked our lives in town, our kids had friends there. This place is a terrific place to raise kids.

“I just didn’t have any inklings of leaving at all. This is where I wanted to be. I just wanted to coach football and I was doing it.”

He remembered a time when there was a rumor that Don Nehlen was leaving for North Carolina and a coach at another school had suggested that move might work well for Kirelawich.

“Do you realize how much your quality of life will go up if you move to North Carolina?” he said.

That set Kirelawich off.

“I said, ‘What the bleep do you know about my quality of life? What the hell are you talking about,” Kirelawich said.

West Virginia meant that much to him. It was his style of life, a style his family could enjoy, one he did not want to change.